About 10 minutes into our meal at Ristorante Cocchi, a huge smile spreads across my face. Our gregarious hosts have just offered me a choice between a glass of sparkling red lambrusco or a crisp and zesty white — both native to the Emilia-Romagna region. When I pause for a nanosecond, a slice of ham en route to my mouth, Fabrizio comes to my rescue. “One now and one later? There’s always another bottle,” he laughs.

In addition to a well-stocked wine cellar at this charming Parma restaurant, there are plates of tortelli flying out of the kitchen, whipped up by their in-house sfoglina (fresh pasta maker), plus cheese and cured meat which keep materializing before my eyes. Just when I think things can’t get any better, someone wheels out a trolley laden with Italian digestivos. It’s no wonder David Beckham names Cocchi as one of the things he misses most about his time spent in Italy while playing for AC Milan.

Basilica di Santa Maria della Steccata in Parma, Italy

With its venn diagram of culture, food and wine, Italy has always been something of a Disneyland for discerning adults. Parma, located in the north — near the top of Italy’s boot — takes gastronomy to Olympic levels of excellence. Naples’ mozzarella and San Marzano–topped pizza, or Rome’s eggy, cheese-dusted towers of carbonara might grab all the headlines, but Parma is a gourmand’s wonderland with an impressive concentration of food products bestowed with a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO). In 2004, Parma was even ordained the seat of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and it was named a UNESCO City of Gastronomy in 2015.

Prosciutto di Parma, used in a number of tasty dishes across Italy, also has a Protected Designation of Origin. It must come from heritage pigs raised in one of 11 regions of Italy

With just over 300,000 inhabitants, Parma is the 15th largest city in Italy and the second most populated in Emilia-Romagna. But what it lacks in scale, it makes up for in significance. The University of Parma is one of the oldest in the world, plus the city is home to 19th-century opera house, Teatro Regio; a frescoed Parma Cathedral; and famous works of art displayed inside La Galleria Nazionale. And yet, this charming pastel-coloured, cobblestoned city, sandwiched conveniently between Milan and Bologna, still falls under most tourists’ radars.

Teatro Regio is a 19th-century opera house in Parma

Of course, Parma is most famous for the eponymous paper-thin, salty ham that I can’t physically restrain myself from gobbling up at every opportunity. Prosciutto di Parma can only be made using the hind legs of heritage breed pigs, raised in only 11 regions of Italy. Pig meat, salt and time is all that goes into the hallowed protein. Delicious though Parma ham may be, it’s not the real reason I’m in Italy. I’m actually here to learn about Parmigiano Reggiano, one of the oldest cheeses in the world. Not the grated parm found in plastic tubs in the aisles of Costco. I’m talking about the real Parmesan: Parmigiano Reggiano, the richly flavoured, crumbly, hard cheese wedges made with raw, unpasteurized cow’s milk.

Prosciutto di Parma hanging in rows

Short ingredient lists are a theme here: Parmigiano Reggiano, or the “King of Cheeses,” as it’s regally dubbed, consists of just milk, salt and rennet. So, aside from it being delicious, what makes it so coveted? Well, unlike me on this trip, Parmigiano-Reggiano cows have a very strict diet. These grass- and hay-fed bovines produce a cheese that has a true terroir and sense of place, and is extremely consistent. It’s even used as a form of currency: Banco Emiliano in Emilia-Romagna is known to accept Parmigiano-Reggiano as collateral for personal loans. Needless to say, it’s pretty special.

On our first morning, we head out to the cheesemaking facility, Parmigiano Reggiano Caseificio, to see for ourselves. The group dons fetching white lab coats, booties and hairnets before heading to the inception point. Here, the trifecta of ingredients is added to large industrial vats and left to work its magic.

When curds begin to form, the factory workers lift and shape the cheese into a giant ball using an implement that is a cross between a giant’s whisk and a pole vaulting stick. Using a piece of cloth, the cheese is then lifted out and tied to a metal pole lain across the vat. The cheese is then cut in half, each swaddled and attached so that it dangles above the water.

Though it’s cumbersome and requires two bodies for this part of the waltz, the workers move swiftly and delicately, cradling the cheese baby with grace. The cheese is later submerged into water with several of its brothers and sisters, before reemerging from the salt bath like a delicious phoenix 12 months (or more) later.

I’ve seen the tattoo imprinted on the rind of every wedge of Parmesan, but I’ve never really questioned how it got there. The mark of origin is given to the cheese just a few hours after it comes into existence: A stencilling band is fastened around the rind of the cheese, providing PDO and Consortium inscriptions, a dairy identification number, plus the month and year of production. I learn that the rind, unlike some other cheeses, is not made of wax or added afterwards — it’s simply the product of the hardened exterior being washed in brine.

The authentication process might seem arduous, but with profits of counterfeit Parmesan estimated at over $2 billion globally, it’s still not enough to protect the famous formaggio. In 2021, the Parmigiano Reggiano Consortium announced that they would be trialling digital trackers, embedded into food-safe labels in the fight against copycats.

The best part of the tour has definitely been saved for last. Inside the cheese storage room, or “bank of cheese,” we crane our necks to see the wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano, stacked at least 20 high, as we wander through the rows of cheese in wonder, snapping selfies with the iconic spheres.

Escapism editor Katie Bridges inside Parmigiano Reggiano Caseificio

After 12 months, the wheels of cheese are quality checked by representatives from the Consortium, who tap them with a hammer to listen to the sound they make. Despite a startling resemblance to the drums seen in hippy Trinity Bellwoods circles, the experts are fully dressed and have a purpose: If the sounds are even, the cheese has no cavities. Defects don’t necessarily mean the cheese is headed for the garbage. Minor imperfections are simply downgraded to mezzano, or medium grade, and sold. Some of the cheese stays put, maturing for another year or two into a more intense Parmigiano Reggiano.

Cheese must be quality checked after 12 months

Finally, after so much taste bud teasing, we get a chance to sample some cheese aged for 12, 24 and 36 months to distinguish the difference in flavour and appearance. The youngest is delicate and buttery; cheese aged for 24 months is much more crumbly, with a great balance of salty-sweet; and the oldest one is way more intense with a lot more crunchy cheese “crystals,” the result of amino acids hardening during the aging process.

It’s not just cheese factories touting the virtues of Parmigiano Reggiano: No matter where you dine, the cheese flows freely from the grater in Parma. At trattorias, Parmigiano Reggiano is eaten as an appetizer, and sprinkled liberally over regional pasta dishes like anolini in brodo, tiny parcels of filled pasta swimming in a chicken broth; or tortelli di erbetta, a bigger ravioli-type pasta typically stuffed with ricotta and smothered in butter. Over at Michelin-starred Ristorante Inkiostro, we’re treated to a menu that incorporates Parmigiano Reggiano in each mouth-watering dish, pairing the cheese with everything from venison to a pear and honey dessert.

Almost everywhere we go, we find lambrusco on the menu, a popular everyday sparkling red wine from the region. A visit to Monte delle Vigne winery, perched on the picturesque hills of Ozzano Taro, teaches us a little about the grapes and wine that originated in Emilia-Romagna and nearby Lombardy. Lambrusco is yet another protected product with a controlled-origin designation, which means that it must be made in a specific region, similar to prosecco and champagne. Unlike the overly sugary white lambrusco that I pre-gamed as a university student, this frizzante (lightly sparkling) red wine is typically dry and absolutely delicious. Italians would probably hate me for describing it as crushable — but it’s exactly that.

Thanks to its enviable proximity, we make the 40-minute drive to Modena to explore yet another food hub. Modena may be most famous for the notoriously hard-to-get-a-reservation-at, Michelin-starred Osteria Francescana; the Ferrari and Lamborghini sports cars that whizz around the city’s narrow streets; or even world-famous opera singer Pavarotti, but it’s also known for its balsamic vinegars.

The Barbieri family has been making traditional balsamic vinegar at Acetaia di Giorgio since 1870

After our morning caffè, we head to a stunning old mansion called Acetaia di Giorgio where the Barbieri family has been making traditional balsamic vinegar since 1870. After an adorable Westie by the name of Marlon Brando greets us with kisses, we head up several flights of stairs to a tasting room that looks like a tiny museum.

Traditional balsamic vinegar can only be produced in Modena and neighbouring Reggio Emilia, and must be made from two grapes: lambrusco (red) or trebbiano (white). The pressed grapes are reduced and rotated through a series of barrels for a minimum of 12 years. Each barrel gets progressively smaller, and each year, a little of the older liquid is poured into the next — like a balsamic vinegar Russian doll.

Modena is famous for its balsamic vinegar, which is made using pressed grapes aged in a series of barrels

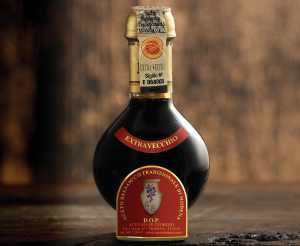

All of these balsamic vinegars are appointed a (you guessed it) PDO, with those aged for 12 years honoured with a white label, while a gold cap indicates that the liquid has been aged for at least 25 years. All traditional balsamic vinegar from Modena comes in a bulb-shaped 100–ml bottle — handy for me, who was able to sneak some back in my carry-on luggage.

When I first received my itinerary, I wished the trip were much, much longer. But as I pack my case, I realize that another day might have proved one food baby too many. Albeit utterly charmed by Parma’s incredible culture of gastronomy (more works of art than food), I’m happy to go home and eat the occasional vegetable. Climate change might pose a challenge to makers of Parmigiano Reggiano in the future — but until then, I say dig in. Parma is a gastronomic utopia that should be on every foodie’s bucket list.

Balsamic Vinegar with a gold cap has been aged for at least 25 years

Once upon a time, I packed travel itineraries with museums and art galleries that I had little interest in, stoically trudging from room to room, eyes glazing over as I read the 50th plaque of the day. But culture comes in many forms, each as worthy as the next. I do believe you can tell as much about a place, its culture and its people from a simple but delicious plate of pasta and a sprinkling of parm. Food might not be hung on gallery walls but I put it on just as high a pedestal, and I intend to let my belly guide my travels forevermore.