The biggest octopus I ever caught with my bare hands weighed five pounds. I was 12, maybe 13. That underwater struggle felt like slaying a kraken. The nest was just deep enough that my lungs were nearly empty by the time I swam down.

Every descent became more painful, my chest screaming for air, as I had at most 10 seconds at the bottom to struggle with the beast before returning to the surface, gasping, sputtering, panting. I still remember the bristle worm I accidentally touched during the fight. The burn seared for hours, like an unrelenting wasp sting. But the pride of showing off my catch to my grandpa, the octopus master, made it worth it.

He first taught me how to catch an octopus four years earlier, on my first day back in Croatia after half a decade away. Maybe it’s that people don’t speak about the horrors of war with a third grader, but I remember jumping into island life mostly ignorant of the years of terror my friends and family had weathered. During the time my family stayed away from Croatia, the country I took my first steps in was shredded by war. While my cousins braved bombings, I went about being a regular Canadian kid. I forgot the language, and the island of Sipan became more of a myth than reality.

Although it’s the largest island in the Elaphiti archipelago, Sipan’s a scant 9.1 kilometres from tip to tail, boasting two villages and 436 residents. Small it may be, but it’s dramatic. Lush, evergreen- and olive-covered mountains that drop into the turquoise sea. Ragged limestone cliffs that beg to be climbed. The harbour, though, is calm. A fishing boat-dotted bay ringed with palm trees and gem-coloured fishing nets drying in the sun. On this tiny fishing island, locals are raised on the hyperboles of a good fishing tale: “It was this big, I swear.”

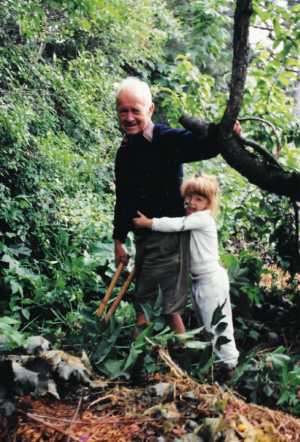

After his stroke, my grandfather struggled with language. This was painful for a man who could previously jump between seven languages effortlessly. I’d only ever heard stories about my grandpa as the fearless Croatian sea captain but the man I knew was a soft-spoken garden putterer and animal whisperer. That first day back on Sipan he jumped off the pier without warning, only to return with a wriggling octopus in his hands. That day, I met the part of my grandpa that had been lost to the stroke.

You develop respect for your dinner once you’ve looked it in the eyes

He passed me the octopus he caught and I stroked its tofu-like skin, letting its tentacles wrap up my arm. After a few minutes, my grandpa decided the creature had suffocated on land long enough. He began slamming the still-pulsing body into the hard concrete. Once the ball of muscle and limbs stopped fighting, he then turned its head inside out, pulling out its organs, rendering the creature completely limp. Some families hike, others play games or go camping. My family's hobby is hunting octopus.

Just as I learned how to hunt from my grandpa, my father learned from his grandpa. When the three of us would return home with our catch, I’d settle into the too-hot kitchen with my grandmother. Although my grandmother was a phenomenal entertainer, she was not a great chef. My grandmother would pound the creature soft and boil it for hours with a cork and a few bay leaves. According to her, the cork made it more tender. That was the next day’s lunch. It was served cold, chopped into a salad with plenty of onions pickled in a red wine vinegar.

Even though the way my grandmother prepared octopus was chewy and unimaginative, I was inspired. Seeing the creature go from sea to plate made clear to me the relationship between death, food and nature. I decided then that if I couldn’t stomach killing my own dinner, I shouldn’t eat animals. For this reason, I spent a swath of my teenage years as a vegetarian. Even today, before I kill an octopus I mutter “sorry” under my breath before biting it between the eyes. (This is a more benevolent way of ending an octopus’s life as the biting method stops brain function in about five seconds rather than three minutes of brutal bashing.)

Local fishermen say their hauls are more meagre every year

While killing an octopus is easy, finding these masters of camouflage isn’t so simple. Octopi are funny because while they don’t want to be found they’re also décor fanatics. Some will have the most easily missed cave (a deep nook in a rocky surface or a burrow under some algae-covered rocks), but then they’ll strew their favourite shells around their homes to create gardens. Some octopi are ostentatious with a love of shiny shells, others prefer a minimalist look: rocks only. Often the currents have gathered some shells together, mimicking octopus decoration, and you’ll spend 30 minutes seeking out nothing.

Once I’ve spotted an octopus, typically a pair of eyes tucked into a crag or sometimes even inside some garbage (I once caught an octopus that had made a home out of a car door), the octopus has already seen me. It will sink down farther into its nest, still watching, waiting. The first descent is key. I’ll swallow as much air as my lungs will hold and dive down, usually about five to eight metres. Before I wrestle the creature from its home, I decide if it’s big enough (the smallest I’ll go is a pound and a half). Then, it’s time to rumble.

Reaching into its cave with a bare hand, I’ll wrap my fingers around the body in an effort to pull the octopus out. The sharp Adriatic rocks cut into my hands as I struggle. A second later, the cephalopod has contorted itself free, leaving me with a handful of ink and forcing me to push farther into the rocks. Houdini would be in awe of these escape artists. Finally, when my lungs are near bursting, it’s time to return to the surface, gulp down air and head back down, hoping that while I’m up top my prey doesn’t flee. Sometimes it will take more than a dozen dives for me to catch just a single octopus. If it’s a particularly large octopus in a particularly difficult cave I’ll use my hook, but it’s always more satisfying to win barehanded. It somehow seems fair to give it a chance to outmanoeuvre me.

Octopus hunting is a tradition in Caroline Aksich’s family. The skill was passed down to her from her grandfather

Every year, I catch fewer octopi. I still love the act, the challenge, seeking them out, but I’ve developed a deep guilt about my seafood consumption. As ocean populations dwindle, I ask myself: is it even sustainable if I only eat fish I catch? For me, these multi-hour adventures are part meditation, an opportunity to dig into some of these important questions. While snorkelling off the coast, I will see men indiscriminately grabbing octopi of any size, some smaller than your thumb. They’ll use hooks or copper sulfate, a blue powder that forces the creatures to flee their crannies so that they’re easily scooped up.

I’m not the only one who has noticed that the Adriatic Sea is growing anemic. Local fishermen regularly comment about how the fish grow smaller every year and their hauls are becoming more meagre. Many acknowledge the need for stronger regulation, but are concerned that the government will intervene in their traditions, imposing taxes on industries and people who are already struggling to make ends meet.

“Almost all recreational fishermen go past the five kilos per day maximum now set by the EU,” says Matko Pojatina, a diver who has made Sipan his summer home. The cheery 39-year-old turns sour when discussing the current state of the Adriatic. He’s frustrated by the nation’s impotent conservation efforts, and thinks the ever-growing tourism industry is partly to blame.

Is it even sustainable if I only eat fish I catch?

While walking home this summer with an impressive catch, I was asked if I was selling octopus to restaurants. Why else would I be putting that kind of effort into catching them, they asked. Apart from the obvious answer – they’re delicious – you develop a respect for your plate when you’ve looked your dinner in the eyes. Each octopus has a personality. Some are fighters who will bite you with their surprisingly powerful parrot-like beaks. Others are pacifists that will settle into your hands once caught, calmly acknowledging the end. These creatures are intelligent and special, but for most tourists they’re just an easily forgotten appetizer.

Since tourism became Croatia’s top economic generator, the coast has become inundated with trashy restaurants peddling “traditional” food (i.e. cheap, easy, boring).That these restaurants turn an incredible creature into something so forgettable is insulting. If you’re going to eat octopus, honour it by seeking out its most traditional preparation: ispod saca. After 40 minutes under smoldering coals, cooking in olive oil with peppers, carrots, parsley, garlic and potatoes, the octopus turns smoky and tender. The seafood feast, which comes to the table in its still bubbling glory, is an appropriate Viking funeral and a fitting end for a worthy opponent.